Corporate strategy: parenting advantage

Parenting advantage is a way of making sense of the portfolio of businesses within such a firm, and identifying which businesses to focus on

The 'corporate' strategy at the heart of a company with several business units is determining which companies to participate in and how best to bring value to those businesses. Parenting advantage is a method of analyzing a company's portfolio of businesses and determining which ones to focus on.

When to use it

● To comprehend how a single corporation's portfolio of enterprises works together.

● Identify possibilities to increase business synergies.

● Identify opportunities to break up the corporation or spin off particular businesses.

Origins

Academics and business people have made a conceptual split between businessunit strategy and corporate-level strategy for many years. General Motors, for example, was one of the first firms to develop different business divisions under a single corporate structure in the 1930s.

Because of Michael Porter's significant theories, much strategy research in the 1980s concentrated on business-level strategy. Corporate strategy has never been as popular, but starting in the late 1980s, numerous key studies, including one by Michael Porter himself, looked at the various ways the parent company might offer value to its divisions. Andrew Campbell, Michael Goold, and their colleagues at Ashridge Strategic Management Centre published a series of books and articles that focused on understanding how the centre (the 'corporate parent') might best offer value to the businesses inside a firm.

Harvard Business School's David Collis and Cynthia Montgomery's research was also influential in influencing how companies produce value that is larger than the sum of its parts.

What it is

A multi-business firm's corporate strategy is the sum of the decisions made by its decision makers. Each company's leaders are in charge of designing its competitive strategy: what markets should they compete in, and what position should they take in those markets? The corporate center's leaders are in charge of designing the firm's corporate strategy: what portfolio of businesses should the firm be in, and how can they bring value to those different businesses?

Because most large companies operate in multiple industries, corporate strategy is crucial. Multi-business firms come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Some companies, such as Unilever, are'related diversified,' meaning they have multiple businesses operating in similar markets with similar underlying skills. Some, like General Electric, are 'unrelated diversified' firms, with businesses ranging from healthcare to financial services to aviation engines. There are also 'holding companies,' such as Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway, which have completely different businesses and make no attempt to create synergies between them.

The majority of corporate strategy thinking applies to related diversified and unrelated diversified organizations, with Andrew Campbell, Michael Goold, and Marcus Alexander's parental advantage concept being the most advanced.

The concept of parenting advantage focuses on the unique value that a parent firm can offer its portfolio of subsidiary units. Every corporate parent provides benefit to its subsidiaries, such as lower borrowing rates or access to a corporate brand. Every corporate parent, on the other hand, destroys some value, maybe because it meddles too much in the specifics of the businesses or because the cost of employing employees at the corporate headquarters is too high. When the value a corporation adds to a business, minus the value it destroys, is greater than what a different corporate parent could produce, it is said to have a parenting advantage.

For example, when Microsoft bought Skype a few years ago, it was betting that it could be a better corporate parent for Skype than, say, Google or Facebook. Microsoft has a parenting advantage to the degree that it has been able to assist Skype in being more successful and connect Skype's offerings with its current communication offerings.

How to use it

The concept of parenting advantage can be put into practice by looking at two key aspects of the relationship between the firm's businesses and the corporate parent.

Understanding the parent's 'value generation' prospects with its enterprises is the first dimension. Top executives at General Electric, for example, feel that transferring knowledge across businesses, particularly through the creation and relocation of highly talented general managers, can add value. In contrast, 3M Corporation effectively shares resources; it has a portfolio of technology owned by the company as a whole, which are pooled and leveraged to develop a wide range of products.

The second component is the risk of value destruction, which occurs when a parent does not fully comprehend the business or when the crucial success factors required to make it function are fundamentally at odds with the parental qualities.

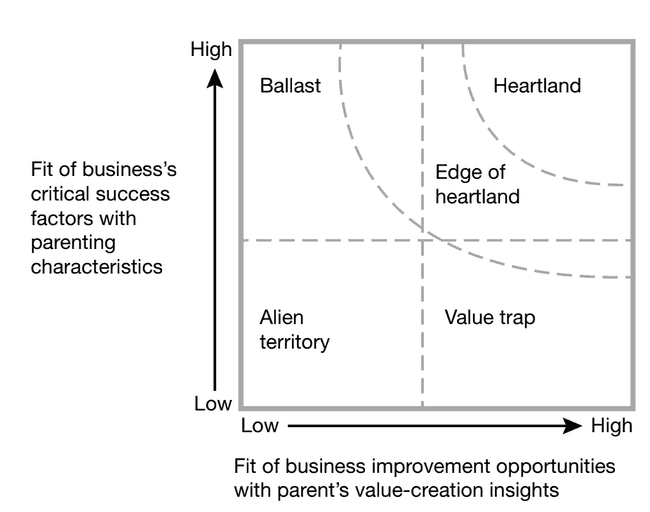

With these dimensions in mind, you can create a matrix that focuses on each business's relationship with the parent in terms of business improvement opportunities (horizontal dimension) and the potential for the parent to destroy value by failing to meet critical success factors (vertical dimension) (vertical dimension). The heartland firms provide the foundation of the company; they operate in locations that the parent company leaders are familiar with, and they often profit greatly from being part of the larger organization. Firms on the outskirts of the heartland are known as edge-of-heartland businesses.

Alien territory businesses, on the other hand, are poorly understood by the parent and risk being mismanaged or neglected. Normally, they should be sold as quickly as feasible.

Ballast businesses are ones that the parent understands well but where, given the rest of the portfolio, there are little prospects to generate value. For example, a conventional core business (like as IBM's old mainframe business as it transitioned to software and services) is frequently ballast, in the sense that it is massive and profitable but offers little prospects for added value. Ballast can be beneficial because it gives the company solidity and weight, but it also slows things down. Ballast businesses are often sold off sooner or later — IBM, for example, eventually sold its PC division.

Ballast enterprises are the polar opposite of value traps. In such circumstances, the parent may have insight into how they might improve, but there are also components of misfit that will likely result in value loss. There was rationale in GE buying an investment bank (Kidder Peabody), for example, because it offered GE access to banking expertise while also benefiting the bank from GE's cheap cost of capital. However, Kidder Peabody's arrogant and bonus-driven culture clashed with GE's, and a rogue trader caused the company to lose hundreds of millions of dollars. The company was wisely sold by GE. In general, unless a parent can discover a means to better fit its own characteristics with those of its value-trap firms, it's usually best to divest them.

Top practical tip

Top pitfall

Further reading

Campbell, A., Goold, M. and Alexander, M. (1995) ‘Corporate strategy: The quest for parenting advantage’, Harvard Business Review, 73(2): 120–132.

Collis, D.J. and Montgomery, C.A. (1997) Corporate Strategy: Resources and the scope of the firm. Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin.

Porter, M.E. (1987) ‘From competitive advantage to corporate strategy’, Harvard Business Review, 65(3): 43–59.