Disruptive innovation

Innovation is the engine of change in most industries

In most industries, innovation is the catalyst for change. However, there are some industries where innovation affects incumbent leaders (for example, digital imaging and Kodak), and others where innovation benefits incumbent leaders (for example, video on demand and Netflix). Clay Christensen developed his theory of innovation to assist solve this puzzle. He demonstrated that some innovations have disruptive characteristics while others have sustaining characteristics. Knowing which is which is quite useful.

When to use it

● When an industry undergoes change, it can be difficult to determine who the winners and losers are.

● To determine whether a new technology is a threat or an opportunity.

● To determine how your company should respond.

Origins

Over the years, academic study has focused heavily on innovation. Most people begin with Joseph Schumpeter's concept of 'creative destruction,' which says that the process of innovation produces new products and technologies at the expense of previous ones. When the personal computer became popular, companies that made typewriters were all 'destroyed.'

However, not every innovation leads to creative destruction; in other cases, it can serve to strengthen companies that are already successful. Kim Clark and Rebecca Henderson's 1990 study addressed this issue by demonstrating that the most damaging innovations (from the perspective of existing enterprises) were architectural innovations, which changed the way the entire business system worked.

Clay Christensen, whose PhD dissertation was supervised by Kim Clark, went this theory a step further by proposing that some new technologies are disruptive: they have a significant impact on the industry, but established firms are reluctant to adapt because of how they develop. The Innovator's Dilemma was released in 1997, and The Innovator's Solution (with Michael Raynor) was published in 2003. Christensen's concepts were first published in a 1995 paper with Joe Bower, and subsequently expanded in two books, The Innovator's Dilemma and The Innovator's Solution.

Christensen's theories regarding disruptive innovation have become tremendously famous, both because they are extremely insightful and because the internet's arrival in 1995 resulted in significant upheaval in many industries over the next decade.

What it is

A disruptive innovation is one that aids in the creation of a new market. The introduction of digital imaging technology, for example, created a new market for creating, sharing, and altering photographs, displacing the previous economy based on film, cameras, and prints. Kodak was shuttered, and new companies with new products, such as Instagram, arose to take its place.

Sustaining innovation, on the other hand, does not generate new markets, but rather serves to improve current ones, allowing firms to compete against each other's sustaining improvements. Electronic transactions in banking, for example, were thought to disrupt the industry, but they actually helped to keep the current leaders in place.

Christensen's theory explains why companies like Kodak have struggled to adapt to digital imaging. One argument would be that existing leaders failed to recognize emerging innovations, but this is rarely the case. For example, Kodak was well aware of the threat of digitisation, and in the 1980s, it even produced the world's first digital camera.

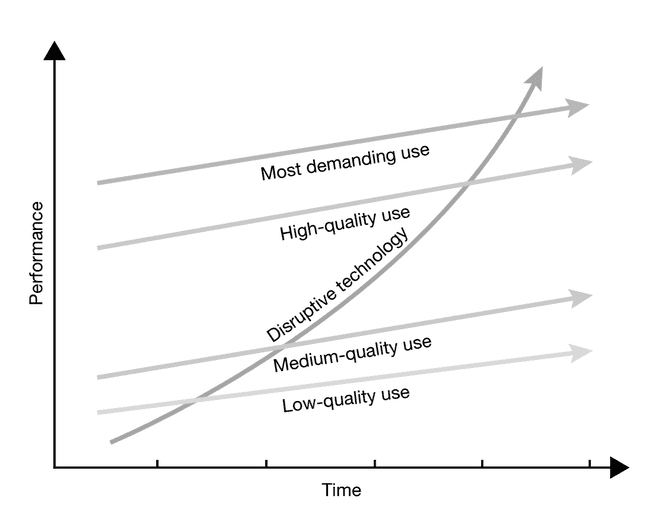

In truth, established enterprises are frequently aware of disruptive technologies, but they are not a threat when they are in the early stages of development — they typically perform a poor job of helping to satisfy the market's existing needs. For example, the first digital cameras had very low resolution. The aim for a well-established company like Kodak is to listen to and respond to the requirements of its greatest consumers, which requires increasingly complex adaptations of current products and services.

Disruptive innovations may begin with low-quality products, but can improve with time and eventually become 'good enough' to compete head-to-head with some of the market's existing offers. With the introduction of digital cameras in the early 2000s, and then cameras built into early smartphones, this transformation occurred in the world of photography. During this period of transition, established companies generally continue to invest in new technologies, but not very actively - because they are still profitable with their traditional technology.

New enterprises, on the other hand, enter the market and put their entire weight behind disruptive technologies. They frequently identify new services (such as online photo sharing) and progressively erode market share from established enterprises. It is frequently too late for an established organization to respond once it has fully recognized the threat posed by disruptive innovation. Kodak attempted to recast itself as an imaging firm during the most of the 2000s, but it lacked the capacity to do so and was hampered throughout by the difficulty of shifting out of its previous business model.

In essence, disruptive innovations tend to 'come from below' – they are frequently very simple technologies or new ways of doing things that are neglected by existing corporations because they only serve the demands of low-end customers, or even non-customers. However, their progress is so rapid and significant that they end up disrupting the existing market.

How to use it

Disruptive inventions are clearly attractive to start-up companies, and many venture capitalists actively seek out opportunities to invest in them. The more intriguing topic is how established businesses may use this knowledge of disruptive advances to help them safeguard themselves. The following is some basic advice:

● Keep watch of developing technologies: New technologies are constantly emerging in most industries, and as an established organization, you must keep track of them. Most of these technologies either have no commercial applications or assist you improve your existing products or services (what Christensen refers to as "sustaining innovations"). However, a handful of them have the potential to be game-changing developments, and these are the ones to keep an eye on. Investing in small businesses that use these technologies and investing in R&D is frequently a good option.

● Monitor the innovation's growth trajectory: If you see an innovation that is creating a new market or selling to low-end customers, you should keep track of how successful it is. Some low-cost technologies have been stuck in the market. Some advance (for example, through faster computer processing speeds) to meet the demands of higher-end clients. These are the ones that have the potential to be disruptive.

● Create a distinct business unit to commercialize the disruptive innovation: If the disruptive innovation appears to be a threat, the appropriate response is to create a new business unit to commercialize the potential. This business unit should be given permission to cannibalize sales from other business units and to disregard standard company procedures and norms in order to respond rapidly. The new business unit can act like a start-up company since it is given a lot of liberty. If it is a success, you can then consider how to connect its actions to those of the rest of the company.

Top practical tip

If you're concerned about the possibility of disruptive innovation, your company should cultivate traits like paranoia and humility. Being 'paranoid' involves being aware of any potential technologies that could harm your company. And being 'humble' involves considering the demands of both low-end and high-end clients.

Top pitfall

Further reading

Christensen, C.M. and Bower, J.L. (1996) ‘Customer power, strategic investment, and the failure of leading firms’, Strategic Management Journal, 17(3): 197–218.

Christensen, C.M. (1997) The Innovator’s Dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Christensen, C.M. and Raynor, M.E. (2003) The Innovator’s Solution. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Henderson, R. and Clark, C. (1990) ‘Architectural innovation: The reconfiguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established firms’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1): 9–30.

Lepore, J. (2014) ‘The disruption machine: What the gospel of innovation gets wrong’, The New Yorker, 23 June.