Cognitive biases in decision making

John Kotter’s eight-step model for change management

A cognitive bias is an irrational way of interpreting and responding on data. You might hire a job candidate because they went to the same high school as you. It's critical to understand how cognitive biases function because there are so many different varieties, each having both positive and negative consequences.

When to use it

● To understand how you make decisions so you don't make bad ones.

● To understand how others arrive at their points of view in disputes.

● To influence the decision-making processes at your company.br>

Origins

While research on cognitive biases has a long history, most people consider Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman to be the "fathers" of the field. In the 1960s, they conducted research to determine why people make incorrect decisions so frequently. At the time, most people believed in the 'rational choice theory,' which stated that humans will make logical and sensible decisions based on the information available. However, they established that this is not the case. When faced with the chance of losing £1,000, people become risk cautious, whereas the prospect of winning the same amount of money motivates them to take risks. This revelation helped them build an entirely new view on decision-making, among other things. Humans do not use algorithms in the same way that computers do. They instead rely on heuristics, or "rules of thumb," which are simple to calculate but lead to systemic errors.

Kahneman and Tversky's study sparked a slew of other investigations in domains beyond psychology, including health and political science. The field of economics has more recently adopted similar ideas, leading to the creation of behavioural economics and Kahneman's Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002.

What it is

Cognitive bias refers to the mental processes that might lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, or irrational interpretation.

Cognitive biases come in a variety of forms. Some influence decision-making, such as the well-known tendency for groups to default to consensus ('group thought') or to overlook the truth in obtained data ('representativeness').

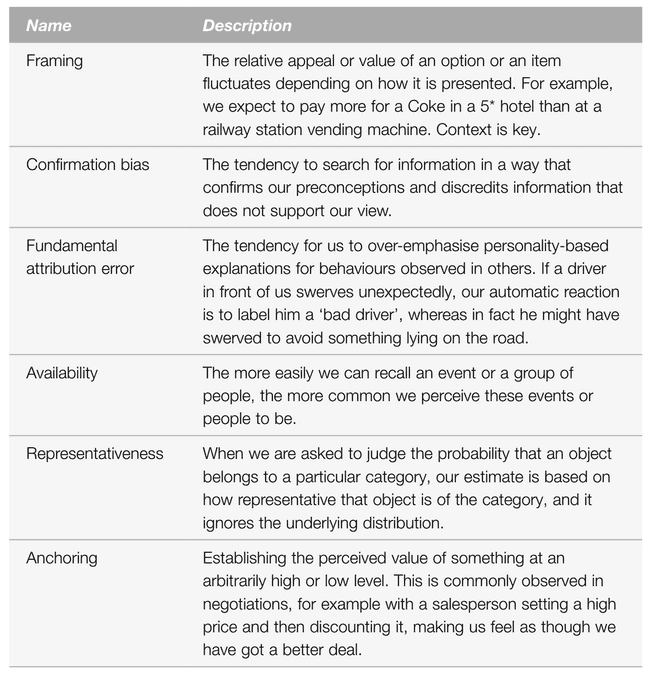

Some have an effect on individual judgment, such as making something appear more likely because of what it is associated to ('illusory correlation'), while others have an effect on memory, such as comparing prior beliefs to current attitudes ('consistency bias'). Biases like the demand for a favorable self-image ('egocentric bias') influence individual motivation. The table below lists some of the most well-known examples of cognitive biases.

How to use it

The most typical way to use cognitive biases in the workplace is to recognize them and then take steps to limit their negative effects. Consider the case below: You're in a business meeting, and you've been asked to decide whether to go ahead with a product launch plan. As a result of your knowledge of cognitive biases, you ask yourself a series of questions:

● Is there reason to suspect the advisors are prejudiced, for example, in their appraisal of the potential market size, or are they seeking to persuade the group to reach a conclusion based on how they have framed the problem?

● Was there a lively debate going on around the table? Did people get an opportunity to voice their concerns? Was all relevant information brought forward throughout the discussion? Or were the voices of minorities silenced?

Any biases you feel are present based on this study are your duty to correct. If you suspect someone is being selective with the data they offer, you can, for example, ask an impartial expert to provide their own set of data. You can have someone provide a counter-argument if you consider a meeting has reached an agreement too rapidly. Indeed, one of the meeting chairman's most essential responsibilities is to be aware of these potential biases and to use his or her expertise to prevent making catastrophic errors.

Other aspects of organizational work follow a similar pattern. When discussing a subordinate's performance or conversing with a potential customer, you must always be mindful of their cognitive biases and how they may obstruct a favorable outcome. Because there are so many cognitive biases, mastering this method will take years of practice.

Top practical tip

Top pitfalls

Another significant difficulty is that recognizing cognitive biases in others is far easier than recognizing them in oneself, so don't think you're immune to bias. Ask others to assist you in this by challenging your assumptions and alerting you if you're sliding into one of the pitfalls we've discussed.

Further reading

Kahneman, D. (2012) Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books. Rosenzweig, P. (2007) The Halo Effect. New York: Free Press. Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R. (2008) Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.